Understanding the deeper methodologies driving white privilege education

I started writing because of my experience in social work education. During the first semester, my professor flat out stated I was not fit for the profession because I opposed concepts like social justice and white privilege. They taught us America was a nation of systemic racism where white people have privileges that minorities do not have. Therefore, white people benefit from a system of oppression and, failing to question it means we are racist. This is the textbook definition of white privilege and it based on something called critical race theory.

This was alarming to me because I realized they were stoking the flames of discontent and if not stopped, hatred and anger towards white people would only grow. How could it not? Students were being trained to believe that white people had the privilege of living in a society that was designed only for them. A decade later, white privilege education has grown into an uncontrollable monster. People driven by the need to find racism behind every corner are overwhelming our education system.

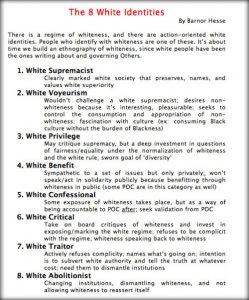

For instance, in New York City, an elementary school principal has encouraged parents to evaluate the eight identities of whiteness which range from being a full-blown white supremacist on one end to an all-out white abolitionist on the other. The term white abolitionist means denying whiteness altogether to dismantle systematic power and privilege. The eight identities of whiteness allow white people to identify their own racism and where they are in their attempts to eliminate it. Only by working to completely dismantle white hegemony can one expect to overcome their own bigotry.

This is like the Helms racial identity model found in an article entitled Owning Whiteness: The Reinvention of Self and Practice (Blitz, 2008) in the Journal of Emotional Abuse. Under this model, whiteness is broken down into six categories. Contact, disintegration, reintegration, pseudo-independence, immersion/emergence, and autonomy. These phases start with a white person being aware of racial differences but being satisfied with the status quo. The next phase realizes that there are social implications to whiteness that cause feelings of guilt. Reintegration involves adopting the attitude that whites have it better than people of color and, denying any responsibility for their own racism. Next, there are the recovery phases, which include white people becoming dependent on persons of color to help them define their racial identity. White people who recover from whiteness (if you will) emerge with new ideas on morality, and how to approach discussions about how other white people deal with their own racism (Blitz, 2008).

Unfortunately, many Americans remain blissfully unaware of how entrenched concepts like Critical Race Theory are in our education system. Having a degree in social work I have the added benefit of knowing where to find the latest news on white privilege education.

For example, the journal Understanding and Dismantling Privilege published an article entitled Considerations for Using Critical Theory and Critical Context Analysis: A Research Note. (Perez Huber, Gonzalez & Solorzano, 2018) The purpose of the article is to examine the best methods of determining whether there is racial bias in children’s books and the theoretical framework in which they should identify this bias. As a student at Liberty University, I took a class where we interpreted various stories through the lens of critical theory. This would entail any perspective that challenges what the left refers to as, the normative power structures. When examining children’s books for racial bias through a theoretical perspective like CRT, they are looking for anything that can fit that framework, even if the author did not intend it.

Along with CRT, the journal article above discusses two other theoretical perspectives from which they examine power and privilege. Critical multicultural analysis and critical context analysis. The first examines power relationships, looking for hidden ways in which dominant cultural ideologies are oppressing minorities. For example, if immigrants in a children’s book were portrayed as Mexican, Perez Huber, et al (2018), would claim the book is suggesting all Mexicans are immigrants. This is not true, of course, but for examining so-called hidden biases and implementing change, this would be the claim. Critical context analysis focuses on examining sociocultural elements of a story that may identify which characters may or may not have power and whose perspective the story is being told from (Perez Huber et al 2018).

The larger point of Perez Huber et al’s article is the merging of these three theories to frame a theoretical approach to implementing CRT in all aspects of education. Critical context and multicultural analysis’ are the research methodologies being used to question children’s literature and, identify what the left would view as racist or biased. CRT is a way of interpreting it. Because critical race theory is just a theory, there is no truth in any of it. Much of this is based purely on the pre-existing biases of those conducting the studies. They are looking for racism because they are critical race theory scholars who, in the absence of race theories, would have nothing better to do than twiddle their thumbs.

It is one thing to understand that they are teaching our children they are racists for being white. Taking the time to understand the perspectives and methodologies they operate from, to teach such things, is what we need if we are going to do something about it. They use theories like white privilege and critical race theory, along with words like systematic oppression to silence opposition and keep people afraid of speaking up.

The justifications used to prove this racism are laughable and only justified through the left’s ridiculous definitions of racism. For example, in the University of Oklahoma’s Master of Social Work Program I attended in 2013, we had a textbook that suggested a black woman was depressed because she sold herself out to the white man’s economic system and lost touch with her historic roots of oppression. As ridiculous as that sounds, the same concept is highlighted in the journal article I discussed. A critical analysis of the short story The Circuit, which is primarily about the triumphs of an immigrant and his journey to America, still highlights a system of white hegemony because the main character is pursuing the American dream (Perez Huber et al 2018). The implication being that the American culture is superior. According to Perez Huber et al (2018), the story pushes a racist narrative by focusing on the American dream and not the journey of the immigrant and, the struggles he endured as an immigrant.

It is hoped that by writing articles like this I am making readers aware of the deeper methodologies the left is using to push their theories. At the end of chapter one of the book, The Naked Communist, Cleon Skousen said if we could just study and come to understand the problem of Marxism, we may be able to save humanity. Unfortunately, he said this nearly seventy years ago and since that time, the left’s agenda has advanced almost unnoticed in terms of how deeply they have infiltrated our educational institutions. We must understand what it is they are doing if we stand any chance of defeating it on an ideological level. My intent is to give readers the opportunity to review these sources for themselves.

.

Methodologies of Critical Race Theory Part Two: Racist Mathematics

In my last article, I discussed some methods being used to examine education through a Critical Race Theory perspective. Critical multicultural analysis and critical contextual analysis are research models used to examine power relationships and the ways dominant cultures allegedly, oppress minorities. These concepts are applied to mathematics as well. Math education has been viewed as a method of teaching problem solving and finding a universal truth through numbers. There are no politics or racial problems in math, it just is what it is. Two plus two will always be four. Critical race theorists, however, have suggested that mathematics education is a vehicle from which power and identity can either be built upon or oppressed because math prowess is a symbol of societal prestige. In this article, I will examine how CRT applies in math by reviewing an article called The sociopolitical turn in mathematics education, by Rochelle Gutiérrez.

Most people assume the use of CRT in math education suggests the idea that math itself is racist because minorities are not as capable. Looking at the attitudes of the political left and how they have argued the need for a welfare state and other programs like affirmative action, this is a fair assumption. This is the same attitude that prompts someone like President Biden to suggest minorities are not smart enough to use a computer to find the closest place to receive a vaccine. Democrats seem to argue that minorities need the government to create a level playing field. Critical race theory in math goes a little deeper than arguing math is a social construct that promotes racism because of a so-called achievement gap. CRT examines how individual power and identity develop based on the power structures determining what minority students should learn about math (Gutierrez, 2013).

Like all aspects of our society, the political left has turned something as politically neutral as mathematics into a quest for social justice. Gutierrez (2013) argues math is a human invention. Therefore, it deals with issues of power and domination (Gutierrez, 2013). In my last article, I showed that much of this perspective represents a pre-existing bias, an already formed opinion that America is a racist society. By applying CRT to mathematics education, leftists scholars are seeking to transform mathematics in a way they suggest, balances societal privilege (Gutierrez, 2013). The key to achieving this, Gutierrez (2013) argues, is realizing politics in mathematics and other educational endeavors exist because they are man-made constructs. In other words, they are looking for racism where none exists. For example, in their book Critical Race Theory in Education, Adrienne Dixon and Celia Rosseau admit their ideas are assumed, and not proven. They reject the idea of equality under the law, and other aspects of American society as a matter of preferring their own theoretical perspectives. They are choosing to look for racism under an already existing assumption that it exists everywhere.

Citing the book Literacy: Reading the Word & the World by Paulo Freire and Donaldo Pereira Macedo, Gutierrez (2013) highlights that the purpose of teaching social justice in math is to allow learners to identify their place within the dominant power structure and, analyze data in a way that allows them to expose injustices in society. Mathematics teachers using the CRT perspective should be working, Gutierrez (2013) claims, to deconstruct racism and show how “whiteness” is the dominant cultural viewpoint. Challenging assumptions about racial hierarchies should be the driving factor in applying CRT to mathematics education.

The development of an individual’s identity through a CRT perspective is a bit complex, and in many ways, a social construct of its own that allows them to make claims of racial domination and oppression. This is the perspective that suggests math is a racist power structure. Gutierrez (2013) argues that identity is not only defined by the individual but from the lens of others around them. This may be true, to a degree. What she is saying is that math is racist and a tool of social oppression because they teach it from a perspective of white normality. Gutierrez (2013) notes that success in math carries a certain prestige and that people who are unsuccessful in math are less smart than those who excel in it. She also refers, as many leftists do, to American meritocracy as a myth. Meaning the idea that we are all equally capable if we apply ourselves is something that is largely, untrue. This coincides with the attitude of the left that minorities need affirmative action and other programs to make things equal. Gutierrez is proving that it is the left’s demented worldview that sees minorities as being incapable.

All math education should focus on carrying students as far as their abilities allow them to go. When ability and merit, however, are nothing but constructive myths, and the education system itself, something that is taught through the perspective of one dominant culture alone, this becomes an impossibility. Gutierrez (2013) argues that teaching math only to lessen the so-called achievement gap perpetuates whiteness and racism because it does not consider issues of identity. This is because the left views achievement also, from the perspective of white normality. In other words, comparing the abilities of minority students to standards held for white students perpetuates racism.

“Recognizing that the identities of individuals are constructed partly through the discourses that operate in mathematics education, we can begin to see how ability is socially constructed. The achievement gap is a perfect example. Although mainly concerned with the well-being of marginalized students (defined here as African American, Latina, American Indian/indigenous, working-class students, and English learners), mathematics education researchers who focus on the achievement gap support practices that often are against the best interests of those students. In fact, “gap gazing” offers little more than a static picture of inequities, supports deficit thinking and negative narratives about marginalized students, accepts a static notion of student identity, relies upon Whites as a comparison group, divides and categorizes students, ignores the largely overlapping distributions of student achievement, offers a “safe” proxy for talking about students of color without naming them, relies upon narrow definitions of learning and equity, and perpetuates the myth that the problem (and therefore solution) is technical in nature” (Gutiérrez, 2008a).

As I have said many times before. You must be a racist in the first place to think like this. Gutierrez is claiming that the perspectives of ability and merit from which they teach math, along with the idea that it is presented from a “position of whiteness,” is what creates the belief that minority students are inferior to whites. As if math itself is a construct that only white people understand. Gutierrez also claims that failing to teach math from a perspective that addresses issues of identity and power reduces students to nothing less than a standardized test score. This I agree with. Standardized tests are something that lowers standards for all students. I would also argue, however, that turning math into a sociopolitical issue, framing it from the perspective of people who have nothing better to do than find race in every issue for transformative change, has more to do with the idea that minorities are disadvantaged.

The lens from which the left views this issue is so black and white. It is as if there are no minority students who excel in mathematics. This is the problem with leftist thinking in general. They fail to recognize people on an individual level. They are obsessed with race because they are the ones who believe in the myth of white supremacy. I am terrible at math. I had to drop out of a metallurgy program because I could not grasp advanced trigonometry. Because of that, I naturally drifted towards something I was more suited for. Based on the left’s logic, are we to believe that there are no blacks or Hispanics that are good at math? Perhaps the larger problem here is that the truths of merit and individual efforts have been rejected by the left because they are determined to tear down the fabric of society so that they can build one to their own liking. One, no less, they refuse to see has failed time and time again. Perhaps the larger problem is that Critical Race Theory itself is the real social construct, based on Critical Theory, thought up by people looking to transform society from one of individualism to collectivism.

Dixon, A. D., & Rousseau, C. K. (2006). Critical race theory in education: All god’s children got a song. New York: Routledge. D

Freire, P., & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy: Reading the word and the world. New York: Routledge

Gutiérrez, R. (2008a). A “gap gazing” fetish in mathematics education? Problematizing research on the achievement gap. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 39(4), pp. 357–364.

Gutiérrez, R. (2013). The sociopolitical turn in mathematics education. Journal for research in mathematics education, 44(1), pp. 37-68